石如飞白木如籀,写竹还于八法通;若也有人能会此,方知书画本来同。Poem on the left side: Rocks are Feibai and trees are Zhou (both are writing techniques in Chinese calligraphy)…If one understands this, one

Colour of Chinese Calligraphy and Sino-Calligraphism

Once in one of the discussion classes at University of Arts in Berlin, I presented some of my calligraphy exercises. They were water-based ink colours (red, blue and black) on A3-sized plain white watercolour paper, and lined up horizontally on the wall. The rest of the story wasn’t so surprising. My dear professor and colleagues must have had enough experience to have images of classic Chinese calligraphy registered in their minds as soon as they heard the word “Chinese calligraphy". So, with good reasons, they unanimously took issue with the formal legitimacy of my colourful doodles that claimed to be Chinese calligraphy, such as the format of paper or the colour of ink. I gave my explanation: the colors are randomly delegated, like the pronunciation of Chinese characters in ideographs, or the meaning of German in epigraphs. Apparently, this answer failed to reassure my international audience, who looked at me as if I were speaking Chinese to them. Days later after that discussion class, I came to a revelation: it might be that my Chinese calligraphy pieces were mistakenly regarded as a rendering of the notoriously influential Abstract expressionism by my international friends.

Whether such a hypothesis is true or not, I think it would be an interesting proposition, namely, does a modernist piece of Chinese ink looks similar to a painting of Abstract Expressionism in the US, or of the Art Informel movement in Europe that swept the art world more than half a century ago?

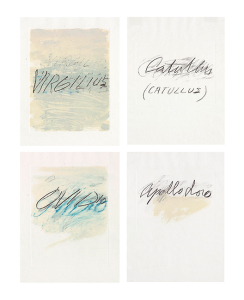

Western art after Modernism was widely influenced by Orientalism. Unlike the early Modernists, who were fascinated by the decorative elements of eastern art, a group of avant-garde artists before and after the Second World War absorbed elements from the concepts of Zen, calligraphy, and ink and formed a calligraphic painting style, such as Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Cy Twombly, who were the representatives of the Abstract Expressionist movement (the New York School) in the United States, and Antoni Tapies and Yves Klein of the European Art Informel movement during the same period. Outside of the realm of painting, the art movement of Happening and Fluxus can also be categorised under the line of eastern-influenced. An artwork of Chinese ink and an Abstract Expressionist painting are obviously not the same thing at all, but what if, cosmetically, they could reach the point of confusion? This is not uncommon, especially in China's modern and contemporary art scene post to Cultural Revolution, where various attempts have been made to mimic, or localise, the western art movements. Needless to say, traditional Chinese ink-and-wash works have also accomplished a modernist transformation in theme and form, not without being influenced by the practices of some pioneering Japanese avant-garde artists, such as Inoue Yuichi.

Chinese calligraphy is not only an art form, but also a method, which is not only the method of calligraphy itself, but also the method of Chinese painting. For practitioners of Chinese ink, there is no such thing as separated act of writing and act of painting. The moment where an ink work manifests itself as calligraphy or painting, is the moment where observers conduct an assessment toward its image. When a Chinese calligraphy cannot be identified by such a perspective that comprehends the meaning of texts, calligraphy consequently becomes painting. That is to say, in the artistic practice of Sino-calligraphism, when a pattern or motif ceases to operate as a logographic symbol of meaning and becomes non-literal, calligraphy becomes painting, and vice versa.

A poem shall not be finished.

Should it be overfilled, it becomes calligraphy.

Should it be misread, it becomes painting.

—— Su Dongpo

We should realize opportunely that, from oracle bones to simplified Chinese characters, Chinese characters are words of images. Despite several iterations, the task of a symbol is not to replace the symbol, and the new Chinese characters will not be a replacement for the old ones, but will continue to co-exist with all the versions that already exist. Writing to words is writing to images that have been identified as symbolic styles, therefore writing to images other than the symbolic styles becomes the act of drawing. The special thing about “Shu” (write), the central verb in Chinese literati ink practice, is that it incorporates “Hua”(paint) as well. In other words, painting is part of writing, a concept that has another, more precise expression: “Xie Yi” (meaning writing). “Xie Yi” is a proprietary term in Chinese Ink art theory, which summarizes the overall methodology of literati ink and wash practices - “writing" as the motivation for making, brush, ink, water, paper as the material carriers, the body, and space-time as the mediums, and meaning writing as the purpose of the chain of actions, which is ultimately situated between the spectrums of symbolic and non-symbolic patterning. and ultimately placed between the spectrum of symbolic and non-symbolic patterns.

At this point, I would like to come back to the topic of the beginning of this article. Non-black-and-white color calligraphy is just a modernist answer to the use of calligraphy as a method. For the sake of terminological clarity, I have named this "method": Sino-calligraphism. With the ambition of reaching a general overview of traditional Chinese ink practice, Sino-calligraphism appeals to a unified school of art, rather than cutting off two separate forms of calligraphy and painting. The reason why it is "Calligraphism" rather than “Calligraphy-and-Painting-ism“ is because, as argued earlier, the law of calligraphy embraces the law of painting. The Chinese character is the image itself, so both the act of painting and the act of writing as a means of reproducing the image are, on an operational level, the same kind of act, i.e., a artistic practice of sino-calligraphism .

Undeniably, fundamentalist Chinese ink works commonly appear in black and white in order to align with tradition. But under the concept of Sino-calligraphism, when calligraphy is used as a method rather than a form, the dualistic relationship of white paper and black ink is not embodied in colour, but in nature of their media during the course of the act of writing or painting. The empty paper isn’t just a white surface but rather a carrier of blankness, a void state that previous to the happening; the brush and ink are also not just substantial materials but represent a methodology, which coin the happening into forms through their materiality. In this process, ink converts the figurative act of waving brushes into a format that paper is competent to read. Paper cannot read the happening directly, but it can read ink, regardless of its colour.

Chinese ink and wash emphasises tradition, a tradition that involves the maintenance of a coherent appearance of the work under the relationship of mastery. But an artistic practice that uses calligraphy as a method can ignore tradition and materials altogether. The artistic practice of Sino-calligraphism does not limit itself to materials, but only construes itself in terms of its law, which can be roughly summarised in the following three characteristics.

Time and space associated with the production of the work are also incorporated into the expression of the work;

Performative features, corporeality and episodicity;

Content-based writing of meaning, or what can be understood as scholasticity.

So it seems that Sino-calligraphism does overlap with Abstract Expressionism and the Art Informel movement on a number of points. And because of their pre-eminence, western calligraphic painting, action painting, as well as Happening, largely occupy the vocabulary that Sino-calligraphism may use in editing its discourse in contemporary contexts, even though the motifs and aesthetic intuitions that it points to are largely distinct from the artworks of western cultural contexts. Indeed, the tradition of Chinese ink art is so deeply rooted yet ubiquitous in east-asian aesthetics that its pervasive pressure in the culture makes its absence inconceivable to the extent that it cannot be clearly identified. In a sense, Sino-calligraphism, as a cultural intuition, is its own victim.

Out of my own interest in studio practice, I have developed some nonsensical thoughts about the concepts and forms of traditional Chinese ink art, until I have unashamedly coined the term "Chinese Calligraphy". I have no facility of vouching for the rigour of this term, but I think it has at least provided me with new perspectives in observing the art scene across time and culture, and a description of the ethos of east-asian art that I have been so wishfully convinced of: restrained yet indulgent, sane yet poetic.

书法的颜色和中华书法主义

在柏林艺术大学的某次创作讨论课上,我展示了几件书法习作。习作呈A3尺寸,材料为普通水彩纸和彩色水性颜料(黑、蓝、红),横排于墙面。想必我的老师同学们都具备足够的艺术史知识和经验,在听到「中国书法」四个字时就立即有了经典中国书法之图像注册在眼前。于是,有法可依地,他们一致对这面前这几张自诩为书法的彩色涂鸦产生了质疑,尤其是它们在颜色方面的另类选择。我给出了我的解释:颜色是随机委派的,就像是表意文字的汉字的发音,或表音文字的德语的意指。显然,这样的解答没能使我的国际观众们如释重负,他们看我的眼神就好像是我在对他们讲汉语。那堂课后,我意识到某种存在于双方观看中的错位使我们彼此困惑。一番大脑斗争后,我竟得出了一个大胆的假设:是否存在一种可能,即,我的国际朋友们错把我的书法当成某种抽象表现主义画作的呈现了。

无论这样的假设属实与否,我想它都将是一个有趣的命题:中国水墨与大半个世纪前横扫世界的美国抽象表现主义(Abstract Expressionsm)或欧洲的无形主义运动(Art Informel)究竟看起来相似吗?

现代主义以后的西方艺术受到了东方主义的广泛影响,不同于现代派早期对东方主义的艺术中装饰元素的着迷,二战前后的一批前卫艺术家从禅宗、书法、水墨的基础观念中吸收元素,形成了书法派的绘画风格,例如在美国兴起的抽象表现主义运动(纽约学校)的代表人物Jackson Pollock (杰克森·波洛克)、Robert Motherwell (罗伯特·马瑟韦尔)、Cy Twombly (赛·托姆布雷),以及同一时期欧洲的无形式艺术运动(Art Informel)的Antoni Tapies (安東尼·塔皮埃斯)、Yves Klein (伊夫·克莱因)。跳出绘画的范畴,偶发艺术、激浪派,也可归为东方主义这一体系。一幅中国水墨作品与一张抽象表现主义的绘画显然完全不是一回事,但如果从外观上看,它们可以达到混淆的程度呢?这种情况并不罕见,尤其是在中国文革以后的现当代艺术场域的各种尝试,又重新将西方二十世纪的艺术运动逐一进行了本土化。中国传统水墨也在主题和形式上完成了现代主义的改造,当然,这其间也不乏受到在日本前卫派,如井上有一,在水墨上的先驱实践的影响。

传统来看,中国书法不仅是艺术形式,还是方法,它不仅是书法自身的方法,还是水墨画的方法。所谓「书画同源」,我的理解是,对于水墨书画的创作者来说,不存在分裂的书法与绘画两种艺术实践,而一幅水墨作品向书和画两种形态分裂的时刻,其实正是观看者对其图像进行审判的时刻。换句话说,中国水墨传统下的创作,是在作品宣告完成并被展示后的观看阶段才被区分为书和画——在每个个体观众的差异化的观看中,当一个图案停止了作为符号意义的运营,成为非符号,书法即为绘画。反之亦然。

诗不能尽,溢而为书,变而为画。 ——苏轼

我们应该及时地意识到,从甲骨文到简体字,汉字是图像的文字。尽管几经迭代,但符号的任务不是替代符号,新汉字也不会是旧汉字的替代品,而是继续与已经存在的所有版本共同存在。对字的书写是对已被确定为符号样式的图像的书写;对符号样式之外的图像的书写,则为水墨画。「书」是中国文人水墨实践的核心动词,它的特别之处在于它将「画」也收编在内。也就是说,「画」是「书」的一部分,这个概念还有另外一个更精准的表述:写意。「写意」是中国书画理论中的专有术语,它概括了文人水墨创作的总体方法论——以「书写」为下笔落墨的动机,以材料载体(笔、墨、水、纸),身体和时空为媒介,以书写「意」为一连串动作的目的,并最终将其安置于符号图样与非符号图样的光谱之间。

如此,绕回文章开头的议题,非黑墨白纸的彩色书法只是以书法作为「法」时的一种现代主义的答案。为了词条清晰,我为这种「法」取名:中华书法主义 (Sino-calligraphism)。为达成对传统中国水墨实践的总体概括的野心,中华书法主义诉求的是一个统一的艺术流派,而不是将书与画二者切割,只取书法。之所以是「书法主义」而不是「书画主义」,是因为,如前文论证的那样,书的「法」就是画的「法」。汉字即图像本身,无论是以再现图像为手段的绘画行为还是以再现图像为手段的书写行为,从操作层面来看,是同一种行为,即,中华书法主义下的创作行为。

不置可否,原教旨主义的中国水墨作品为了与传统对齐,普遍以黑白色的面貌出现。但是在中华书法主义的观念下,当书法作为「法」而不是一种形式时,白纸与黑墨的二元论关系,并不体现在颜色上,而是虚实上。纸代表的是空虚的载体,它是事件未发生前的空白状态;墨代表的是充实的物质,它将一连串的运笔的行为带来的结果反映在载体之上;纸是空间媒介,墨是时间媒介。在这一过程中,材料将行动的书写转译成适配于载体阅读的格式。纸不能直接阅读事件,但可以阅读墨汁,无论墨汁的颜色是红还是蓝。

中国水墨讲究传统,这种传统包含了师承关系下对作品外观的连贯性的维护。而中华书法主义的艺术实践并不对材料加以限制,仅在「法」上对自身进行解释,大致可总结为以下三点特征:

将与作品的生产相关联的时间和空间也纳入作品的表达之中;

表演特征,身体性和偶发性;

基于内容的意义书写,或可理解为学者性。

如此看来,中华书法主义与抽象表现主义和无形艺术运动的确在很多要点上重合了。并且由于先发优势,西方书法派绘画,行动绘画,以及过程艺术和偶发艺术,基本占据了中华书法主义在当代语境中编辑话语时可能用到的词汇表,尽管后者所指向的创作动机和审美直觉很大程度上区别于西方文化语境下的创造。实际上,中华书法主义的传统在东亚美学活动中无处不在,其在文化中的渗透压的使它的缺席变得不可想象,以至它无法被清晰地辨认。某种意义上,中华书法主义,作为一种文化直觉,是它自己的牺牲品。

出于我自己的创作实践时左顾右盼的兴趣,生发出了一些对中国传统艺术概念和形态的无稽的思考,直至毫不知羞愧地发明了「中华书法主义」这一术语名词。这个名词的严谨性有多少值得推敲我无从担保,但我认为它至少为我在观察跨跃时空和文化的艺术现场时提供了新的角度,也为我一直以来确信的东方性的艺术气韵提供了一次共性描述:抑制的也是放纵的,理智的也是诗意的。

related work:a Calligraphy Piece 书法之一(Mo/30)